Blockchain and real estate: A global revolution in the making?

Blockchain has the potential to revolutionise the way real estate is managed and transacted globally.

9 min read

Subscribe

Stay current on your favorite topics

Blockchain has the potential to revolutionise the way the real estate sector operates, from smart contracts to management and execution of property sales and leases, and to the adoption by land registries

In 2008, bitcoin announced itself as the first blockchain application, introducing the world to distributed ledger technology —a secure and transparent peer-to-peer payment protocol. Fast-forward a decade and blockchain is transforming the way global business is done—across industries. In the financial services sector, fintech companies are deploying blockchain to enable retailers and consumers to deal with each other directly, disintermediating lenders. In the mining industry, blockchain is used to track the entire diamond supply chain to ensure that the stones are ethically sourced. In the global fishing business, blockchain is helping to improve tuna traceability and stop illegal and unsustainable practices. Blockchain has also found applications in energy trading and car manufacturing—and it also has the potential to revolutionise the global real estate industry.

What is blockchain?

In a traditional database, data is stored and managed from a single source. In a blockchain environment, data storage and management is decentralised. Here, one public record or database (often referred to as a 'ledger') is distributed across a network of computers (a 'decentralised peer-to-peer network'). The database is secured by sophisticated cryptography safeguarded by so-called 'miners'— computers that process transactions and ultimately verify that they can be uploaded to the database. The network can either be completely public and available for any user who is interested in participating, or private meaning that only designated users have the ability to participate. Every new transaction or information 'block' added to a blockchain is immediately available for every network participant. The need to transfer information from one party to another or separately record and store that information falls completely away.

The blockchain database grows exponentially in this way, forming a comprehensive record of all transactions that have occurred since the database's inception. Once recorded, it is impossible for data to be removed, edited or revised—the data is immutable and resistant to fraudulent modification.

But the data in this environment is only as reliable as the entity or person who is recording it, and so will need verification. For real estate, this will require collaboration between traditional data providers: appraisers, due diligence providers, notaries, and brokers.

46%

of Deloitte's blockchain survey respondents say they would be comfortable using a smart contract instead of a paper-based contractSource: Deloitte

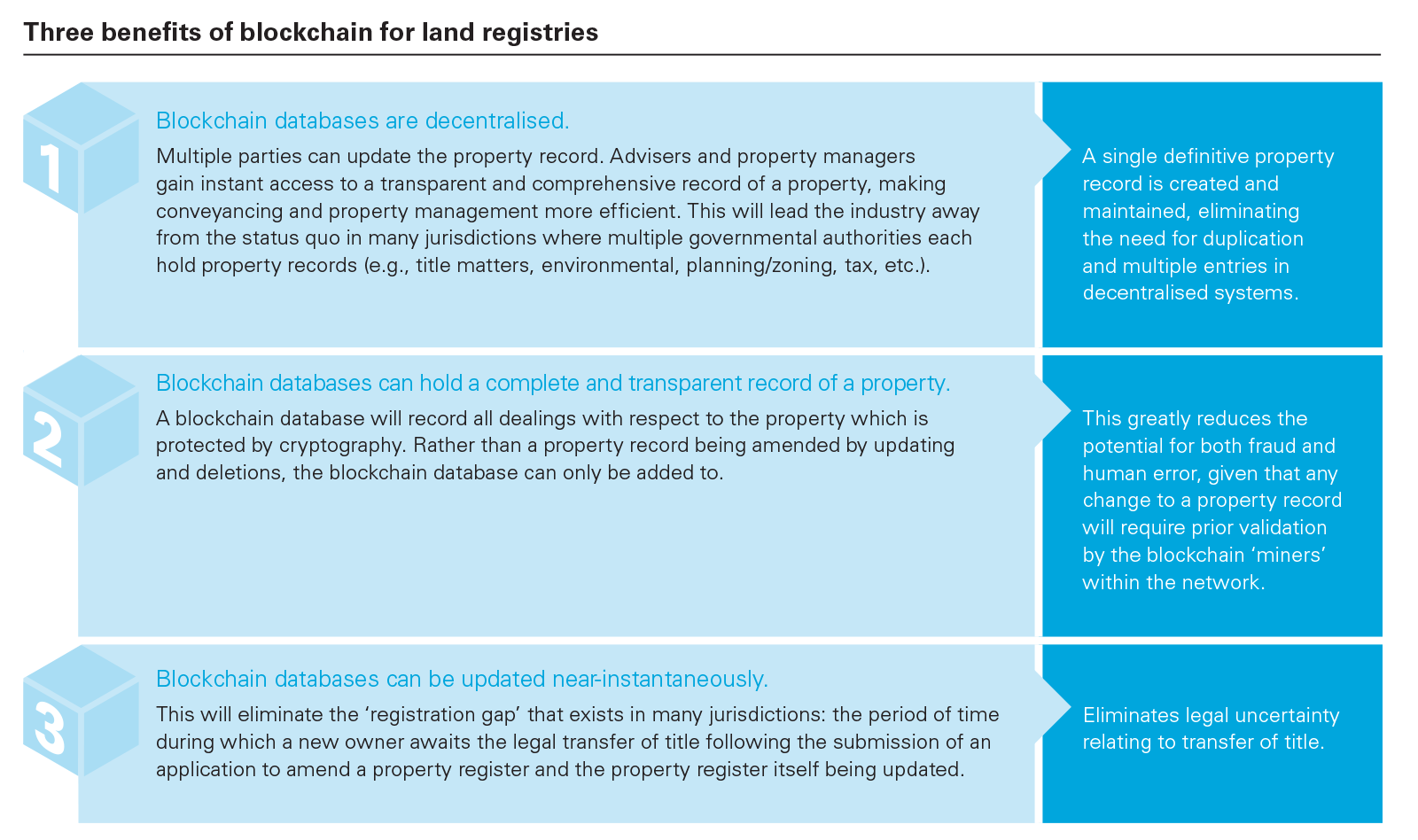

Blockchain in land registration

Real estate is full of registries: Governments or courts often maintain multiple registries of who owns what land and the various interests affecting it; brokers must keep a registry of investors and what shares they own; and landlords have registries of their tenants. There are many issues with these registries, which are often slow, disparate and uncoordinated. In the US, for example, records are kept by individual counties, each with different standards and protocols, making interoperability a problem. In Dubai, there is one central entity that all real estate transactions must go through, creating a slow, expensive and paper-heavy process. Blockchain—at its core, a new type of registry—appears tailor-made to address these challenges by digitising a traditional land registry and moving the industry away from its historic and now technologically outdated models.

A blockchain-based land registry will have all the same functionality— tracking property titles, ensuring single-ownership, keeping a seamless and near-instantaneous record of all transactions and third parties' rights—but with the added advantage of streamlining and enhancing the way real estate transactions are logged and executed. "Using a blockchain as a shared registry has the potential to make investing, transacting and renting real estate cheaper, more efficient and more transparent," said Joseph Lubin, Founder of ConsenSys, a US-based blockchain software technology company.

Smart contracts

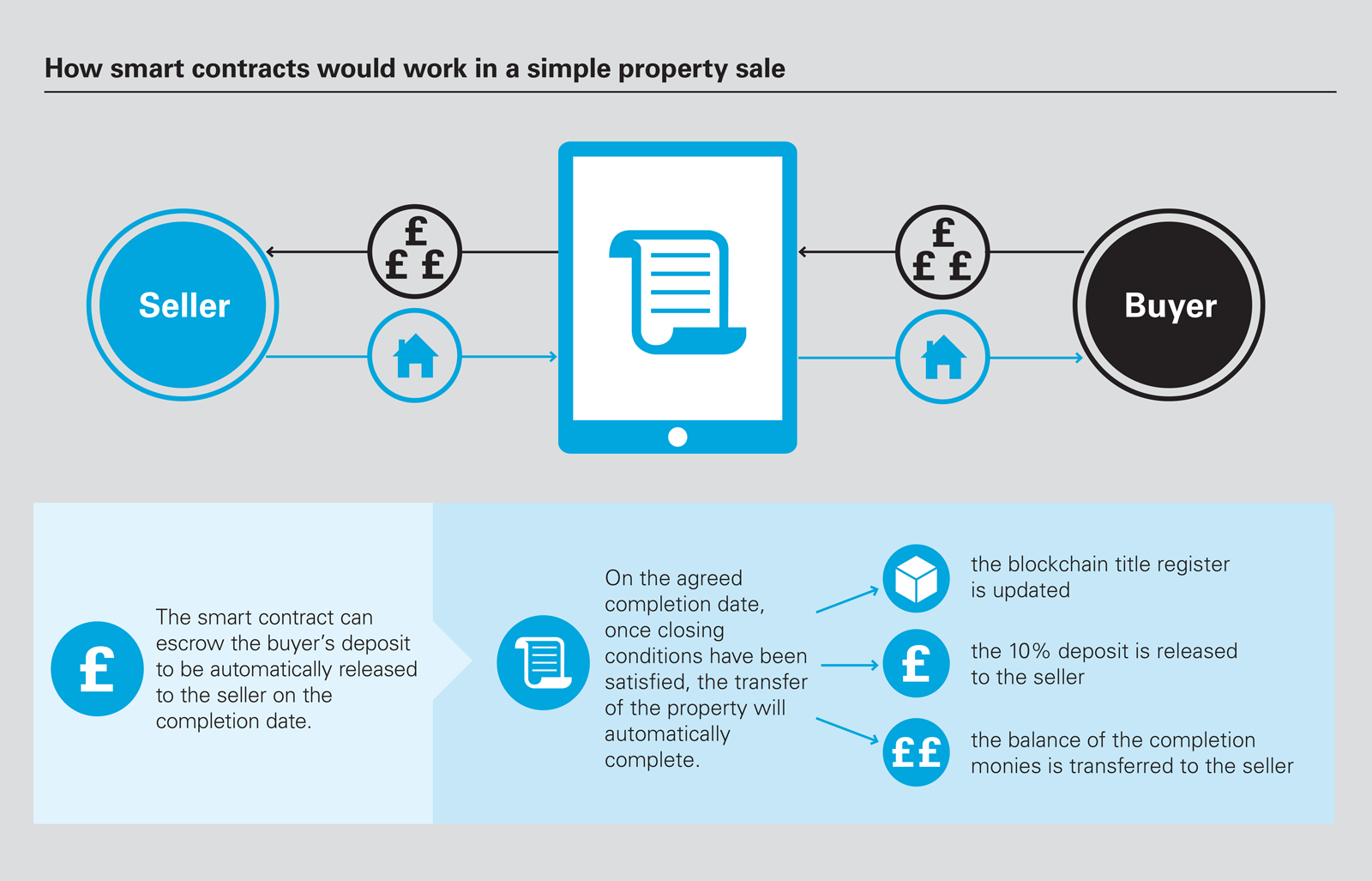

The benefits to the real estate industry go beyond the creation of an 'alternative' land registry. A combination of blockchain and so-called 'smart contracts' in property sales, purchases or leases could likewise transform the industry. Smart contracts administer and execute without the need for human interaction. In commoditised real estate transactions such as residential conveyancing, smart contracts could reduce or even eliminate the need for lawyers and other intermediaries.

Many legal agreements are complex and contain provisions that are never actually used by the parties in practice. But by using blockchain, property service agreements with clear delivery targets and penalty regimes can be administered automatically in ways that have not been previously possible. For example, datacenter 'smart contract' service agreements that require an operator to provide a customer with specific power, temperature and humidity requirements would automatically award the customer service credits if sensors in the facility detect a breach. These contracts can be built into a blockchain database and could be self-executing without human intervention.

Real estate asset and property management

Asset management could also be streamlined by blockchain technology by making property more accessible and liquid as an asset class with all relevant data available on a single online platform. This has obvious attractions for owners, prospective purchasers and tenants. "Not only does distributed ledger technology offer opportunities to streamline the existing process, it also opens up new market opportunities", explains Alex Edds, Director of Innovation at JLL. "The concept of buying shares in a real estate asset anywhere in the world is made more viable through the use of blockchain."

Another possible application is in relation to property management and maintenance. For example, if all maintenance and services for the technical building equipment is recorded in a blockchain, the condition of a property can be easily reviewed and assessed by the owner, tenants and potential buyers, and reduce the need for technical due diligence.

Certain estimates suggest that nearly US$1 billion is spent annually on title fraud resolutions

Source: Inside Bitcoins, December 4, 2015

Building a new technological world order

Blockchain databases can be a tool for increasing efficiency, transparency and security for real estate transactions—providing a secure, permanent record that will speed up transactions, reduce costs and create a unified single registry accessible to all parties.

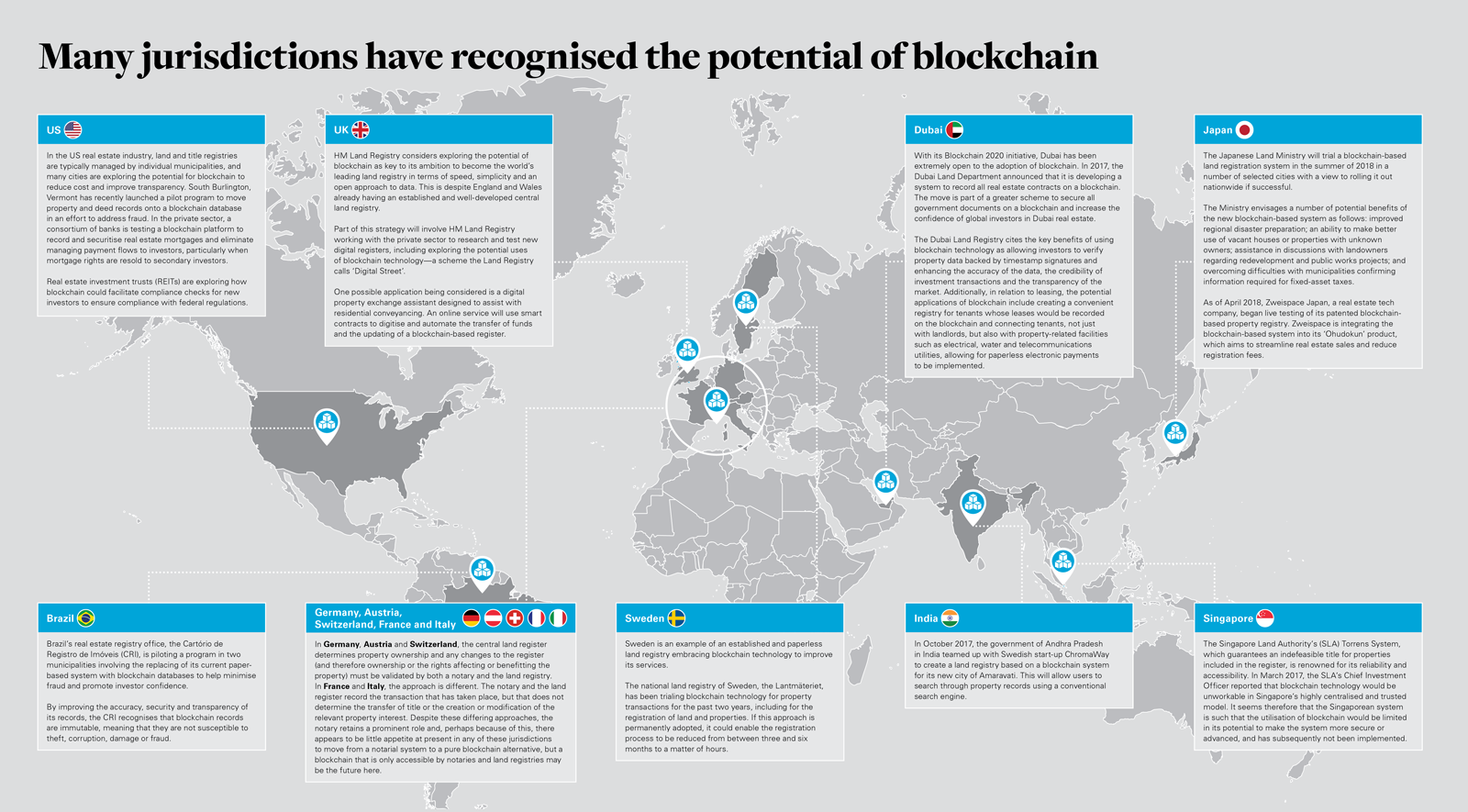

But the adoption of the new technology is going to vary greatly between industries and jurisdictions. Creating blockchain-based land registries may be appealing in countries that seek to encourage overseas investors and have less mature central land registries, as in certain parts of the Middle East, for instance. But more developed European jurisdictions, such as Germany and France, which took a long time to introduce digital signatures and electronic contracts, are likely to take a more cautious approach to the adoption of blockchain, particularly in an industry such as real estate which has historically been regarded as conservative.

"In developed markets, a top-down approach is the ideal solution," says Mohammad Shaikh, Co-founder of Meridio, ConSensys's real estate branch. Existing land registries must be converted to a consistent format, and the gatekeepers of those registries must agree to transfer their data to the new system and eventually relinquish some control. In emerging markets where registries are in their infancy, a bottom-up approach could work better. Individuals must agree to certain standards for recording data, and the registry is built up by individuals and small organizations who want to claim ownership of real estate and make transactions. "In both cases, for widespread adoption there will likely need to be government acceptance of these registries as the source of truth," says Shaikh.

In Germany, for instance, moving to a blockchain database controlled by the courts would enhance efficiency. Signing and closing of transactions, including registration of title or mortgages, could be completed in a single day rather than months. Due diligence of complex easements currently requires a physical visit to a local court and would clearly be much easier if accessible online through public notaries. Further publicly recorded information such as public easements, ground contamination and warfare records, monument protection, etc. could all be recorded in one database which is only accessible to the authorities to make registrations and to public notaries to review and apply for new registrations.

Where gatekeepers are in fact market participants themselves, there will be a particular need for acceptance of the technology underpinning blockchain and distributed ledger technology. But as Edds points out: "Blockchain technology doesn't need to be scary. For the end-user, the experience is exactly the same. Much of the hype of this technology is actually in the back end that doesn't require the end-user to understand the intricacies of how it works. Do you know how your iPhone works?"

40%

of Deloitte's blockchain survey respondents believe there is value in recording existing contracts on the blockchain.Source: Deloitte

Bumps in the road to adoption

If blockchain technology is to succeed, it is crucial that the gap between the technical and legal worlds is successfully bridged, and in many cases there will need to be a fundamental change in the legal approach to address the many challenges that new technology brings.

For example, smart contracts are an appealing proposition, but can the technology accommodate the many facets of a typical commercial contract? After all, smart contracts are neither 'smart' nor 'contracts'. They are self-executing computer programmes, included in a larger economic activity which has its own legal regime concerning non-binary concepts that require a degree of judgment. What is a 'reasonable' period of time? When is a party acting 'unreasonably' or 'improperly'? Outside events or circumstances may influence how a contract is to be performed. What if the property that is being conveyed is damaged or even destroyed between exchange and completion of the smart contract? The market may need to provide insurance solutions to accommodate such scenarios. These questions require an application of the facts to legal concepts and obviously cannot be addressed through smart contracts.

There is also another challenge that has come to the fore with the recent implementation of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). GDPR includes the 'right to be forgotten' if the data is no longer needed for its original purpose. But by default, data entered into blockchain cannot be erased or removed. So on the face of it, blockchain databases in EU Member States appear to be in breach of this requirement. This, too, will need to be addressed.

Many questions still remain, and building trust in the new technology will take time. But one thing is certain: Real estate professionals, law makers, technology developers and regulators must work together to confront the difficulties—and embrace the transformative powers—that blockchain technology can bring to real estate.

Click here to download PDF.

This publication is provided for your convenience and does not constitute legal advice. This publication is protected by copyright.

© 2018 White & Case LLP